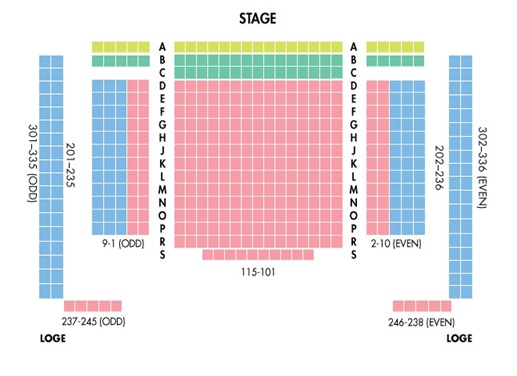

Scaling the house in theatres

Why ‘Cheap seats don’t sell’

The brief

In theatres, the success or failure of a new production can be decided within the first few weeks. With major sunk cost to launch a show, it’s a business that’s prone to major risk.

In the first few performances, empty seats can send a signal that a show isn’t going to succeed. So full houses are important. More generally, empty seats are a wasted revenue opportunity. Any revenue contributes directly to operating cost to run the show as well as towards repaying the sunk cost of a new production.

So what’s the best approach to selling seats?

Theatres have always used discounting to sell late seats – but cutting prices openly devalues a show, and risks a reaction from customers buying at full price. So theatres have to find a formula that delivers their optimum. Most seats sold + most revenue taken.

Open promotion of cheaper seats has been proven to have a negative effect on seat sales. ‘Cheap seats don’t sell’. In fact they slow down sales.

Strategy

By contrast theatres have found that sales of higher priced seats drive sales of the next pricepoint down. This isn’t what you’d expect. Why would customers happily pay more? When you go to the theatre there’s a seductive appeal about seeing the show from the ‘best seats’. Even if different seats at different pricepoints are actually right next to each other. In fact research has shown that theatregoers actually enjoy a show more, when they pay a higher ticket price to see it.

Actions

The established optimum solution for most seats sold + most revenue taken has become a tried and tested formula. The best, or highest priced seats generally sell first, then the next price down etc. High priced seats drive sales of middle-priced seats.

The cheap seats are the ones that tend to be still on sale just days, or at most weeks before the show. These are the seats that theatres will discount to sell, usually by issuing them to discount ticket agencies. Empty seats send bad signals. Higher margins on the seats that they have sold mean that selling what’s not sold through discount ticket agencies reduces margin but delivers a profitable optimum. Of course this doesn’t apply absolutely across every ticket and seat, but it does apply generally.

The big difference

Planning pricepoints – or actually planning ‘relative pricepoints’ is key for theatres. This applies principles of structured relative pricing, of high pricepoints as pricing anchors, of scarcity and availability, and of value attribution which all leverage findings from studies in pricing psychology.

Most seats sold + Most revenue taken. ‘Scaling the house’.